It was still dark, early on a January morning in 2024, when Mohammad Ayas slipped out of the world’s largest refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, and trekked deep into the forest, returning to the place he had fled in 2017. This time, however, he was not escaping the “raining bullets” that had killed his father – he was going back to train and fight against those responsible for his people’s bloody exodus from Myanmar.

Ayas, a 25-year-old Rohingya refugee who teaches Burmese to children in the camps, tells The Independent that he and thousands like him are now united in their struggle against the Myanmar military and others who stand in their way of “reclaiming their motherland”.

“We are ready. I am ready to die for my people. I don’t care what happens to me in this fight to reclaim our motherland, our rights and our freedom in Myanmar,” Ayas says.

Hundreds of Rohingya refugees like Ayas are volunteering to join armed groups, having spent years in the Kutupalong refugee camps, where more than a million members of the persecuted Muslim minority are living after fleeing Myanmar, according to refugee accounts and aid agency reports.

The Independent spoke to Rohingya refugees, as well as a man described as their commander in the Cox’s Bazar camps, who said they are sneaking out for weeks or months at a time to train with weapons in Myanmar, preparing to return and fight both the military junta and any rebel groups who stand in their way.

Rohingya groups say they have been targeted in massacres and forced conscriptions by both sides amid the civil war that began following the 2021 coup ousting democratically elected leader Aung San Suu Kyi and her party. One Rohingya recruit told The Independent they hoped the situation might change if Suu Kyi were to return to power – but they were no longer willing to wait around for it to happen.

Watch The Independent’s documentary Cancelled: The Rise and Fall of Aung San Suu Kyi

Ayas, the father of a four-year-old girl, says he trained in the jungle for six months, with him and other volunteers moving their tents to different locations every few days to avoid detection. He describes his training routine deep in the jungles of Myanmar, that provide cover for insurgent activities as well as temporary respite for those escaping the brutal civil war.

It starts at the crack of dawn and recruits are woken up by the sound of a whistle, says Ayas, who spent the six months in a training programme.

They begin with basic fitness training before being divided into groups, with some receiving training with arms, ammunition and martial arts, while others go for technical training like handling social media, counter-surveillance, or tracking enemy movements and gathering strategic information.

In the heat of the afternoon, they bathe, eat and relax, before the commander leads a second round of drills.

With no end in sight to Myanmar’s conflict, and as conditions in the camps worsen, more Rohingya refugees may find themselves willing – or forced – to take up arms.

“Our main goal is peace. We want to live peacefully with rights and opportunities in Burma, where both the government and the rebels have taken over our land. We want our motherland back, and we will fight for it,” he says, referring to Myanmar’s colonial-era name, which was changed in 1989.

Ayas, who refused to disclose the name of the group he is training with in Myanmar, claims: “More than 1,000 people have now joined and are training. The recruitment is happening everywhere, in all camps.”

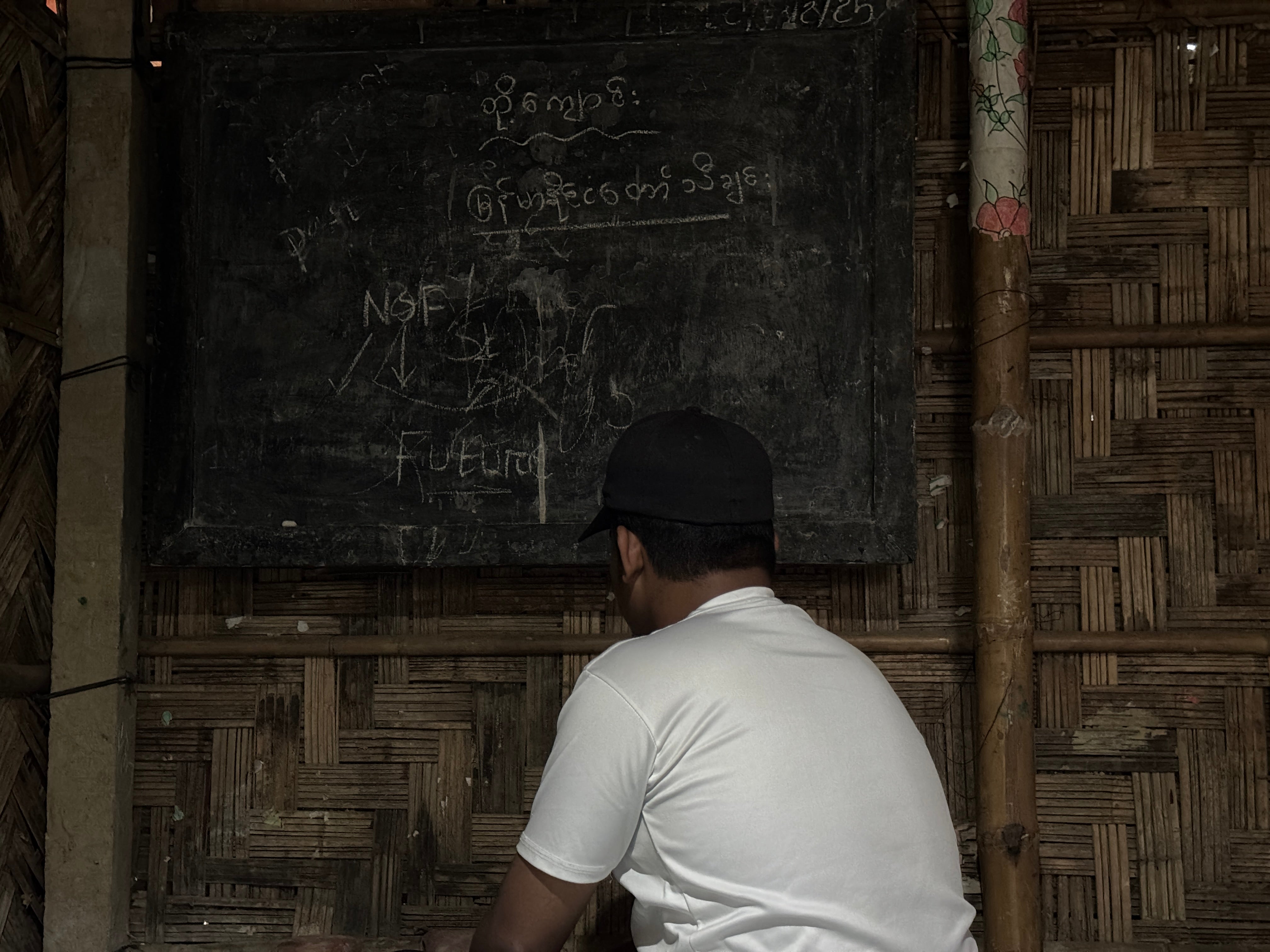

Wearing a cap and tracksuit – unlike the majority of Rohingya men who prefer a simple T-shirt and a longyi or plaid cloth wrapped around the waist – Ayas speaks some English, sometimes forming broken sentences.

Ayas fled Myanmar in 2017 when its military, along with Buddhist militias, began what he describes as the coordinated massacre of entire Rohingya villages, killing men, women, and children alike. The UN has described the violence as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing” with reports of women being raped and entire villages being burned down.

A deepening civil war between Myanmar’s military and armed militia groups has meant that Muslim minorities living in Rakhine State have been attacked by both sides, forcing them to seek safety in Bangladesh, Malaysia, Singapore, India, and Sri Lanka.

Also accused of the systematic persecution of the Rohingya Muslim community is the Arakan Army (AA), a Buddhist militia group formed in 2009 that has gained a foothold in Myanmar and now controls almost all of Rakhine State. The AA claims its objective is to achieve greater autonomy and self-determination for the Arakan people.

Ayas’ family was among the estimated 1 million people who fled the 2017 military campaign. But he had to leave behind his dying father, who was struck by multiple bullets as soldiers “began firing randomly at people”.

“Bullets rained like a monsoon downpour as the military opened fire on people trying to escape. The soldiers were butchering our people,” he recalls, his eyes welling with tears.

Since then, life in the refugee camps has been one of constant struggle, with no future, opportunities, or even basic human rights, he says.

“I am always thinking about going back home. This is not our land, and we do not want to live here anymore,” he adds.

Another recruit, Abu Niyamat Ulla*, 42, works as a religious teacher and is affiliated with Islamic Mahaz, a Rohingya Islamist insurgent group allied with the larger Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO).

“Our first enemy is the military, which is committing genocide on our people, and then the Arakan Army,” he tells The Independent.

Ulla says recruitment efforts have been ongoing in the camps, with men traveling to Myanmar for training and returning to lead seemingly normal lives in the refugee settlements.

“The commander has directed us to target men as young as 18 or 20 who are physically and morally strong for recruitment,” he explains.

“We do not force anyone but ask them if they wish to go back [to Myanmar]. If they are willing, we guide them. The process has already started. People go there for training, return, and then others follow,” he says.

Ulla, who remarried after losing his first wife and has three children, says his people have suffered injustice all their lives while the international community remains focused on wars in Gaza and Ukraine, ignoring the plight of the Rohingya.

He speaks warmly of Suu Kyi’s father Aung San, the independence leader and founding father of Myanmar, who “worked with the Rohingya”. “I hope that if Aung San Suu Kyi is released, she might stand up for us, though I’m not certain she will,” he says.

Instead, he says, the Rohingya need to stand up for themselves. “The time has come for us to defend our lands, our rights, and reclaim our dignity as human beings,” he asserts.

A maze of narrow lanes and alleys in one of the 33 camps leads to the safehouse of a man described by recruits as a senior commander spearheading the recruitment drive and training efforts. His men blend seamlessly into the crowded refugee camp, indistinguishable from the thousands of displaced families around them, forming a loose perimeter as they led The Independent to meet him.

No words were exchanged until the commander, a young man in his mid-30s who gave his name as Raynaing Soe*, sat cross-legged in an armchair and began speaking of his “revolution” to unite the Rohingya community against both the military and the Arakan Army. Soe is a nom de guerre, and he spoke to The Independent on condition of anonymity given the sensitivity of his recruitment activities.

“We would seek peaceful reconciliation first, but if that does not happen and our people continue to die, then we are ready and united to fight for our land,” says Soe, wearing a hat and a T-shirt emblazoned with the word “Strong”.

“The whole Rohingya community has decided to unite. We are working to bring all people onto one platform to fight in Rakhine State, to take back our land and our rights.”

Soe says their attempts to cooperate with the AA against the military have collapsed multiple times since 2021. He refused to disclose his own group’s affiliation.

“They [the AA] do not want to work with the Muslim community. They only want to work for Buddhists. Now, whoever comes in our way – military or AA – we will destroy them to take back our lands.”

While Rohingya recruits in the camp that The Independent spoke to denied allegations of forced conscription, the rights groups and aid agencies that work to provide inhabitants with their basic humanitarian needs have raised concerns over the increase in such drives since the 2021 coup.

There are nearly a dozen armed militia groups active within the camps, according to a report by the Bangladesh ministry of defence. These groups have been blamed for rampant drug dealing, extortion, killings and human trafficking within the camps as well as internal clashes.

The well-known groups include the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO), the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), the Arakan Rohingya Army (ARA), and Islamic Mahaz.

The RSO has been accused of colluding with the military in Myanmar and carrying out forced recruitment of people from the camps to fight against the AA. After gaining a bad reputation for their alleged alignment with the junta, the RSO’s members sometimes go by the alternative name “Maungdaw Militia” to recruit people.

Fortify Rights director John Quinley says they have been investigating Rohingya armed groups for years, collecting testimonies, videos, and audio evidence that recruitment – both voluntary and forced – has been ongoing in the camps.

Quinley says they have testimony from Rohingya refugees as young as 17 years old who were abducted from the camp and taken into Myanmar.

“There’s dwindling humanitarian support in the camps right now. Under both the [Muhammad] Yunus interim government [of Bangladesh] and the former oppressive government of [Sheikh] Hasina, the situation in the camps has been restrictive. Refugees have no freedom of movement and cannot access formal education in any meaningful way.

“Every aspect of Rohingya people’s lives remains restricted. Given these conditions, many Rohingya have taken matters into their own hands, seeking to liberate their community through armed resistance.”

An internal memo by a humanitarian coordination group operating in Bangladesh revealed that nearly 2,000 people were recruited from the refugee camps between March and May last year alone, according to a Fortify Rights report.

It said that the drives used techniques such as “ideological, nationalist and financial inducements, coupled with false promises, threats, and coercion” to recruit people.

The Independent contacted Bangladesh’s Office of the Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner (RRRC), which runs the camps, and the ministry of defence for comment, but has not received a response.

Threatening to add further vulnerability and instability into the mix is US president Donald Trump’s blanket executive order halting the work of USAID. That decision is expected to have a devastating impact on the sprawling refugee camp entirely dependent on outside funding – USAID contributed 55 per cent of all foreign aid for the Rohingya last year, according to some estimates.

Quinley says the result will be more people turning to armed resistance, unless the host government in Bangladesh allows them to access livelihoods or grants them freedom of movement.

“The people I talked to in the refugee camps have a palpable sense of hopelessness. For many Rohingya, one of the few ways to reclaim agency is to say, ‘If I fight, at least I have some control over my fate.’”

“Unless we see real support for Rohingya refugees, there is likely to be an uptick in people joining these militant groups – some willingly, but many out of sheer desperation.”

* Names changed to protect identity